Natural gas is extracted from the Earth by drilling wells into underground rock formations that trap methane-rich gas, then using pressure differences, engineered well designs, and surface processing systems to bring that gas safely to the surface.

Depending on the geology, this can involve conventional vertical drilling, horizontal drilling, hydraulic fracturing, or offshore production systems.

Each method follows a defined technical sequence designed to locate gas-bearing formations, access them without collapsing the well, and control the flow of gas under high pressure.

Where Natural Gas Is Found Underground

Natural gas forms over millions of years from buried organic matter subjected to heat and pressure. It accumulates in porous rock layers such as sandstone or limestone, often sealed beneath impermeable rock like shale or salt. These underground accumulations are called reservoirs. Some reservoirs allow gas to flow freely once drilled, while others trap gas so tightly in the rock matrix that additional stimulation is required.

There are two main geological categories. Conventional gas reservoirs consist of relatively permeable rock where gas migrates naturally and can be extracted through a vertical well.

Unconventional gas reservoirs include shale gas, tight gas, and coalbed methane, where the gas remains locked in low-permeability rock and requires advanced drilling and stimulation techniques.

Locating Gas Before Drilling

Before drilling begins, energy companies conduct extensive subsurface exploration. The most important tool is seismic surveying, which uses controlled sound waves to map underground rock structures. These surveys can identify folds, faults, and reservoir traps several kilometers below the surface.

Exploration data is combined with historical drilling records, rock core samples, and geochemical analysis to estimate gas volume, depth, and pressure. Drilling a single exploratory well can cost anywhere from several million dollars onshore to more than 100 million dollars offshore, so precision at this stage is economically critical.

| Exploration Method | Purpose | Typical Depth Range | Cost Intensity |

| Seismic reflection surveys | Map underground rock layers | 1–10 km | High |

| Exploratory drilling | Confirm gas presence | 1–6 km | Very high |

| Core sampling | Analyze rock porosity and gas content | Reservoir-specific | Medium |

| Well logging | Measure pressure, temperature, and resistivity | Entire wellbore | Medium |

Drilling the Well

Once a site is approved, drilling begins with a rotary drilling rig. A steel drill bit cuts through soil, sediment, and rock while drilling fluid, commonly called drilling mud, circulates through the well. This fluid cools the drill bit, carries rock cuttings to the surface, and maintains pressure inside the well to prevent collapse or uncontrolled gas release.

Modern wells are drilled in stages. Large-diameter sections near the surface are drilled first, then progressively smaller sections extend deeper.

Each section is lined with a steel casing and sealed with cement. This layered casing system isolates groundwater, stabilizes the well, and prevents gas from leaking into surrounding rock formations.

Drilling depth varies widely. Shallow gas wells may reach 1,000 meters, while deep shale gas wells often exceed 4,000 meters, including horizontal sections.

Horizontal Drilling and Hydraulic Fracturing

In low-permeability shale formations, vertical drilling alone is not enough. Horizontal drilling allows the well to turn sideways and run laterally through the gas-bearing layer for up to 3 kilometers. This dramatically increases contact with the reservoir.

Hydraulic fracturing, commonly called fracking, is then used to create microscopic fractures in the rock. A mixture of water, sand, and chemical additives is pumped into the well at extremely high pressure. The pressure opens fractures, and the sand, known as proppant, holds them open so gas can flow.

Hydraulic fracturing does not create large underground voids. Fractures are typically a few millimeters wide and extend tens to hundreds of meters from the wellbore. The process is tightly controlled and occurs thousands of meters below groundwater aquifers.

| Fracturing Component | Function | Typical Proportion |

| Water | Creates pressure | 90–95% |

| Sand or ceramic proppant | Keeps fractures open | 4–9% |

| Chemical additives | Reduce friction, prevent corrosion | <1% |

Bringing Gas to the Surface

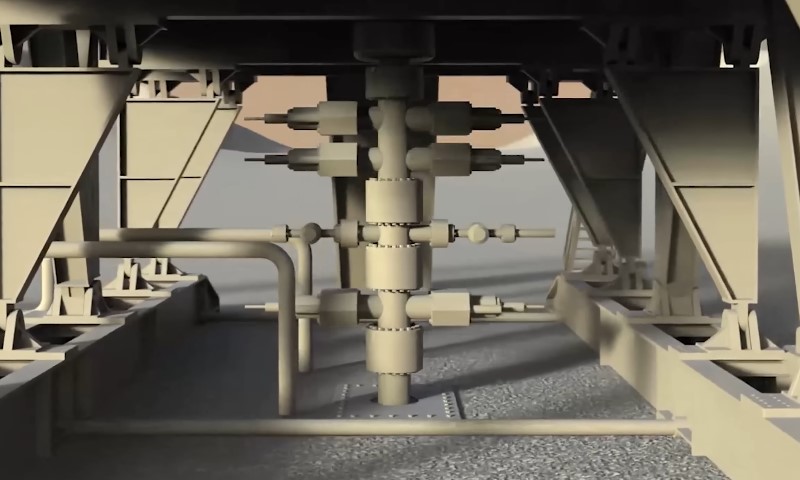

Once the well is completed, pressure inside the reservoir forces gas upward through the wellbore. In high-pressure fields, gas flows naturally without mechanical assistance. As reservoir pressure declines over time, compressors may be installed to maintain flow rates.

At the surface, gas passes through a wellhead assembly designed to control pressure and flow. Safety valves automatically shut the well if abnormal pressure is detected. From there, the raw gas moves to processing facilities.

Processing and Cleaning the Gas

Raw natural gas contains impurities that must be removed before distribution. These include water vapor, carbon dioxide, hydrogen sulfide, nitrogen, and natural gas liquids such as ethane and propane.

Processing plants use dehydration units, absorption towers, and cryogenic separation systems to purify the gas. Water removal prevents pipeline corrosion and freezing. Acid gases like hydrogen sulfide are stripped out for safety and environmental reasons.

After processing, pipeline-quality natural gas is typically over 95 percent methane.

| Processing Step | Removes | Reason |

| Dehydration | Water vapor | Prevent corrosion and freezing |

| Acid gas removal | CO₂, H₂S | Safety and emissions control |

| NGL separation | Ethane, propane, butane | Commercial value |

| Compression | Pressure loss | Pipeline transport |

Offshore Natural Gas Extraction

Offshore gas extraction follows the same fundamental principles but requires specialized infrastructure. Wells are drilled from fixed platforms, floating rigs, or subsea installations. Gas flows from subsea wells through pipelines to processing platforms or directly to shore.

Offshore projects are significantly more expensive due to harsh environmental conditions, deep water, and complex logistics. However, offshore gas fields often contain large, long-lived reservoirs that justify the investment.

Environmental and Safety Controls

Strict engineering and regulatory standards govern natural gas extraction. Well casing integrity, cement quality, pressure monitoring, and methane leak detection are core safety requirements. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas, so minimizing leaks during extraction and transport is a central industry focus.

Modern operations use continuous monitoring systems, infrared leak detection, and automated shutoff valves. In many regions, baseline groundwater testing is required before drilling, followed by post-drilling monitoring.

While extraction techniques have improved significantly since the early shale boom of the mid-2000s, operational discipline remains critical. Most environmental incidents are linked to surface equipment failures rather than subsurface fracturing itself.

Production Decline and Well Lifespan

Natural gas wells do not produce at constant rates. Production typically peaks shortly after completion, then declines. Shale gas wells experience faster decline rates than conventional wells, often losing 60–70 percent of their initial output within the first year.

This decline profile is one reason why shale gas development involves continuous drilling to maintain overall production levels. Conventional gas fields, by contrast, may produce steadily for decades.

| Well Type | Initial Production | Decline Rate | Typical Lifespan |

| Conventional gas well | Moderate | Slow | 20–40 years |

| Shale gas well | High | Rapid | 10–25 years |

| Offshore gas well | High | Moderate | 25–50 years |

How Extraction Methods Shape Global Supply

Advances in drilling and fracturing technology fundamentally reshaped the global natural gas market. Between 2005 and 2020, U.S. natural gas production more than doubled, driven almost entirely by shale development. This shift turned the country from a projected gas importer into one of the world’s largest exporters of liquefied natural gas.

At the same time, extraction costs fell as drilling efficiency improved. Horizontal drilling lengths increased, fracture designs became more precise, and data-driven reservoir modeling reduced dry wells.

These technical gains explain why natural gas remains a central component of energy systems even as renewable generation expands.

Natural gas extraction is not a single technique but a layered engineering process shaped by geology, physics, and economics

. From seismic imaging to steel casing, from fracture design to gas dehydration, every step exists to safely move methane from deep rock formations to end users with predictable flow and controlled risk.