A pure sine wave inverter converts DC power (usually 12 V, 24 V, or 48 V from batteries or solar) into AC power that closely matches utility electricity. In Serbia and most of Europe, “utility-like” means 230 V at 50 Hz with a smooth sinusoidal voltage waveform.

The word “pure” is not marketing poetry. It is shorthand for low harmonic distortion and stable voltage and frequency under load, so devices behave the same way they do on grid power.

The practical reason people buy pure sine wave is simple: modern loads are full of electronics and motors that assume a near-sine input.

When the waveform is stepped or blocky (modified sine), the extra harmonics create heat, noise, erratic behavior, charger issues, and sometimes early failure. The inverter may still “work,” but your equipment does not necessarily like what it is being fed.

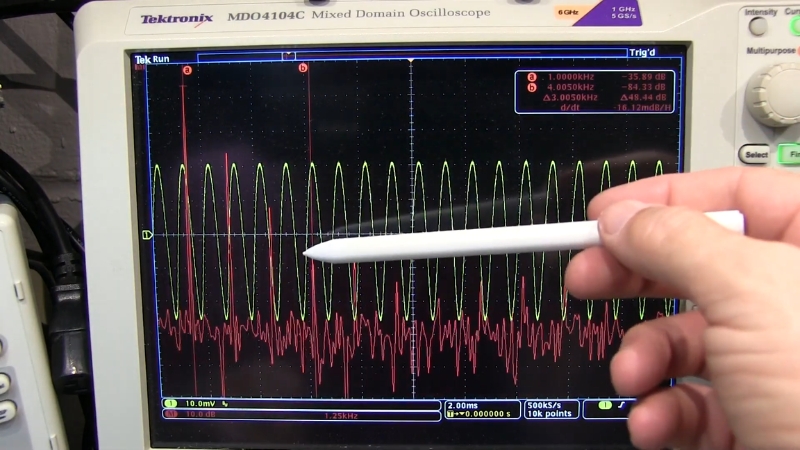

The One Spec That Tells You If The Output Is Truly Clean: THD

If you want one number that correlates strongly with “grid-like,” it is Total Harmonic Distortion (THD). Lower THD means less harmonic content riding on top of the 50 Hz fundamental waveform.

Manufacturers of quality pure sine wave inverters commonly claim THD below about 3% on the AC output.

For context, power-quality standards for public networks are not “0% THD” either. The European EN 50160 standard is widely referenced with a voltage THD limit of 8% (measured up to higher harmonics).

That gap matters: “pure sine” does not mean mathematically perfect. It means clean enough that the equipment sees it as normal power.

A good target when shopping is ≤ 3% THD, and if you plan to run sensitive audio, lab gear, or certain motor drives, aiming low is worth it.

How A Pure Sine Wave Inverter Works In Real Terms

Inside the inverter, DC is first chopped at high frequency using switching transistors (typically MOSFETs or IGBTs). That chopped energy is shaped by control electronics and filtering so the output becomes a smooth 50 Hz sine-like waveform.

Most modern pure sine inverters use a PWM (pulse width modulation) method that creates a high-frequency “staircase” that an LC output filter smooths into a sinusoid.

Then, depending on the design, the inverter also performs voltage conversion (step-up) so a low DC bus can become 230 V AC at the output.

You do not need to memorize the circuitry, but you should understand the consequence: waveform quality depends on control algorithm, switching frequency, output filter, and load behavior.

That is why cheap “pure sine” units sometimes test badly under certain loads, while good units remain clean across load ranges.

Pure Sine vs Modified Sine: What Changes For Your Appliances

Modified sine wave inverters are not “slightly worse.” They output a stepped waveform with high harmonic content.

That harmonic content drives extra losses in inductive loads (motors, transformers) and can confuse power supplies that expect a sine input.

Harmonic currents in motors are specifically associated with overheating, noise, and torque pulsation in induction motor behavior.

Here is the practical comparison that actually helps you decide:

Topic

Pure Sine Wave Inverter

Modified Sine Wave Inverter

Waveform

Smooth, low harmonics

Stepped, high harmonics

THD typical

Often ≤ 3% on reputable units

Often much higher

Motors (fridge, pump, fan)

Runs cooler and quieter

More heat, buzz, lower efficiency, sometimes won’t start reliably

Chargers (laptops, tool batteries)

Usually normal

Some run hotter, noisier, or fail to charge properly

Audio and TV

Lower noise risk

More EMI and audible hum risk

Microwave

Usually fine if sized correctly

Often underperforms or runs hotter

Efficiency and usable power

Typically higher

Often lower because harmonics create losses

Price

Higher

Lower

If you plan to run anything with a motor, anything with a transformer, or anything you care about long-term, pure sine is the safer default.

What Devices Actually Need Pure Sine

A clean way to think about it is not “sensitive vs not sensitive,” but how the device draws power.

Devices Where Pure Sine Is Strongly Recommended

- Refrigerators and freezers (compressor surge current)

- Pumps and fans (induction motors)

- Microwaves (transformer and magnetron behavior varies)

- CPAP, medical equipment, monitoring devices

- Modern TVs, gaming consoles, and audio equipment

- Anything with variable-speed motor drives (some tolerate modified sine poorly)

Devices that Often Tolerate Modified Sine

- Resistive heaters (simple heating elements)

- Incandescent bulbs

- Some basic tools (not all), but performance can still degrade

When in doubt, assume you need pure sine unless you are powering simple resistive loads only.

How To Size A Pure Sine Wave Inverter Correctly

View this post on Instagram

Most inverter problems come from sizing mistakes. Not “wrong brand,” but wrong watts and wrong assumptions about surge.

Step 1: Separate Continuous Watts from Surge Watts

An inverter has a continuous rating and a surge rating (often for a few seconds). Motors and compressors can demand 2× to 6× their running wattage at startup.

If the inverter cannot supply that surge, the appliance may click, stall, or cycle repeatedly.

Load type

Typical starting surge vs running

Fridge/freezer compressor

3× to 6×

Pump

2× to 5×

Power tools (universal motor)

2× to 3×

Microwave

Usually close to rated input, but still wants headroom

Step 2: Add Your Real Simultaneous Loads

You size the inverter for what will run at the same time, not what you own.

Example setup

Running watts

Likely surge requirement

Laptop + router + LED lights

150–250 W

Minimal

RV “normal” (TV, laptop, lights, charger)

400–800 W

Minimal to moderate

Fridge + small appliances

200–600 W running

Surge can exceed 1200–2000 W

Workshop tool use

800–2000 W

Surge can exceed 3000–5000 W

Step 3: Convert AC Watts Into DC Battery Current

This is where people get surprised. A “1000 W” AC load on a 12 V battery system is a huge current.

Use this approximation:

DC amps ≈ AC watts ÷ (battery volts × inverter efficiency)

Assume 0.9 efficiency for a decent inverter at mid-load.

AC load

12 V system (A)

24 V system (A)

48 V system (A)

300 W

~28 A

~14 A

~7 A

600 W

~56 A

~28 A

~14 A

1000 W

~93 A

~46 A

~23 A

2000 W

~185 A

~93 A

~46 A

The takeaway is not the exact amps. The takeaway is that high power on 12 V means extreme current, thick cables, serious fusing, and a battery that can actually supply it without voltage sag.

Runtime: The Battery Math People Skip

Inverters do not create energy. They translate it. Runtime depends on usable battery energy and the load profile.

A practical estimate:

Runtime (hours) ≈ (Battery V × Battery Ah × usable fraction × efficiency) ÷ load watts

Usable fraction depends on chemistry. Lead-acid (AGM/Gel) is typically treated as 50% usable if you want a good lifespan. Lithium can be 80–90% usable in many setups.

Battery bank

Usable energy assumption

Approx usable Wh

12 V 100 Ah AGM/Gel

~50% usable

~600 Wh

12 V 200 Ah AGM/Gel

~50% usable

~1200 Wh

24 V 100 Ah AGM/Gel

~50% usable

~1200 Wh

12 V 100 Ah LiFePO4

~85% usable

~1000 Wh

If you run a 600 W load continuously, a “12 V 100 Ah lead-acid” setup is not an all-day plan. It is closer to “about an hour” once you include real-world losses and voltage drop.

Installation Reality: Cables, Fuses, And Heat Matter More Than Brand

Pure sine wave inverters fail early mostly because of poor installation, not because the circuit is fragile.

DC-side rules that actually prevent problems:

Risk

What causes it

What it looks like

Fix

Voltage drop

Thin/long cables

Inverter alarms, low voltage shutdown

Shorter runs, thicker cable

Overheating

Poor ventilation

Thermal shutdown, shortened lifespan

Airflow, spacing, avoid hot compartments

Arcing/fire

No fuse, loose terminals

Melted lugs, smell, intermittent reset

Proper fuse/breaker near battery, torque terminals

Noise/interference

Bad grounding or routing

Audio hum, radio noise

Better grounding, cable routing, and ferrites if needed

For high-power setups, 24 V or 48 V systems are usually easier to build safely because the current is lower for the same wattage.

What Makes A “Good” Pure Sine Inverter In The Real World

@datoubosss The source factory specializing in the production of pure sine wave inverters! Complete range of models, can load a variety of electrical appliances! #DATOUBOSS #Inverter #pv #Solar #battery ♬ original sound – datoubosss

Ignore marketing adjectives and check measurable features.

Feature to check

Why it matters

Output THD specification

Lower THD correlates with smoother operation and less heat/noise. Reputable pure sine often targets ~3% or less.

Continuous rating at 40°C

Some units rate at unrealistic temperatures; derating is real

Surge rating and duration

Critical for compressors and pumps

Low idle draw

Important for overnight or standby systems

Protections

Overload, overtemp, low voltage, short circuit

Transfer switch / UPS mode (if needed)

Only matters if you want a seamless switchover

Remote monitoring

Useful in RV/solar installs, not mandatory

Also, be suspicious of “pure sine” units that do not publish THD, efficiency, and surge details. That often signals corners were cut.

Pure Sine Inverters In Solar Systems: A Key Clarification

A pure sine inverter in a solar context may refer to different devices:

Inverter type

What it does

Where it fits

Off-grid inverter

Battery DC to 230 V AC

Cabins, RV, backup

Hybrid inverter

Solar + battery management + AC output

Home storage, self-consumption

Grid-tie inverter

Solar DC to AC synchronized with the grid

Feed-in systems, usually no batteries

If you are building around batteries, you care about surge, idle draw, and battery low-voltage behavior. If you are grid-tied, you care about synchronization, anti-islanding, and grid standards.

The Clean Answer: When Pure Sine Is Worth Paying For

Pure sine wave inverters cost more because producing low-distortion AC requires higher-frequency switching, better filtering, tighter control, and typically better components.

The payoff is reduced heat in motors and transformers, fewer weird device behaviors, and less noise and interference.

If your goal is “runs everything like a wall socket,” pure sine is the correct choice. If your goal is “power a heater and a basic lamp cheaply,” modified sine can work, but you are choosing lower power quality on purpose.