A rainwater harvesting system is a setup that collects rainfall from a roof surface, stores it in tanks or cisterns, and reuses that water for specific household purposes such as garden irrigation, toilet flushing, laundry, or in some cases full domestic use after treatment.

For homeowners, the main value lies in reducing dependence on municipal water, lowering utility bills, and maintaining a reliable water source during droughts or restrictions.

In regions with moderate to high annual rainfall, a properly sized system can supply a significant share of a household’s non-potable water demand year-round.

How Residential Rainwater Harvesting Systems Work

At a technical level, rainwater harvesting relies on a simple sequence of steps, but each step has design implications that affect efficiency and water quality. Rain falls onto the roof, which acts as the primary catchment area.

The material and condition of the roof influence both yield and cleanliness. Water is then guided through gutters and downspouts into a pre-filtration stage that removes leaves, grit, and roof debris.

Many systems include a first-flush diverter that discards the initial runoff, which typically contains the highest concentration of dust, bird droppings, and pollutants. The remaining water flows into a storage tank or cistern, where it is held until use.

Depending on the intended application, the stored water may pass through additional filtration or disinfection before distribution.

The physics behind the collection is straightforward. One millimeter of rain falling on one square meter of roof yields one liter of water. This makes system sizing predictable and allows homeowners to estimate potential yield with reasonable accuracy.

Roof Area

Annual Rainfall

Theoretical Collection

100 m²

600 mm

60,000 liters per year

150 m²

800 mm

120,000 liters per year

200 m²

1,000 mm

200,000 liters per year

Losses from evaporation, overflow, and first-flush diversion usually reduce usable yield by 10 to 20 percent.

Key Components of a Home Rainwater Harvesting System

Every residential system consists of several core components, each with a defined role. The catchment surface is typically the roof.

Metal, clay tile, and slate roofs are commonly used because they shed water efficiently and introduce fewer contaminants than older asphalt shingles.

Gutters and downspouts must be correctly sized and sloped to prevent overflow during heavy rain events. Leaf screens and mesh guards reduce maintenance and protect downstream components.

Storage tanks vary widely in material and placement. Above-ground polyethylene tanks are common in small residential installations due to low cost and ease of installation.

Underground concrete or fiberglass cisterns are favored when space is limited or when large volumes are required.

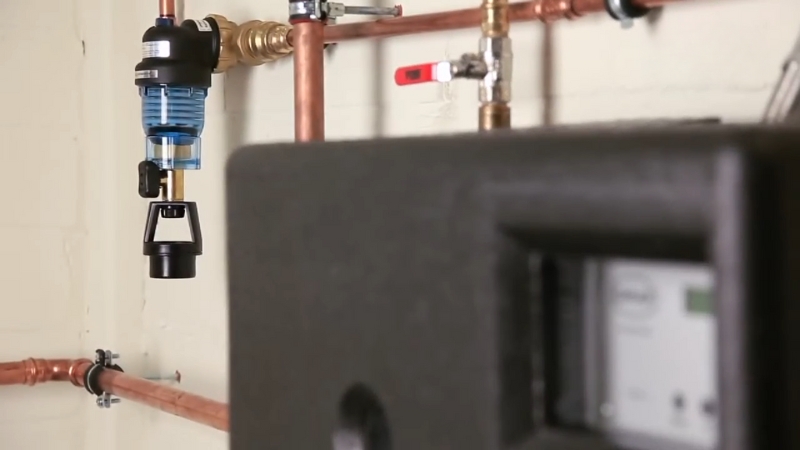

Pumps are necessary when gravity alone cannot supply adequate pressure, particularly for indoor uses. Filtration ranges from simple sediment filters to multi-stage systems that include activated carbon and ultraviolet disinfection.

Common Storage Tank Materials

Material

Typical Capacity

Lifespan

Notes

Polyethylene

1,000–10,000 L

15–25 years

Lightweight, UV-stabilized

Concrete

10,000–50,000 L

40+ years

Durable, reduces algae growth

Steel (lined)

5,000–30,000 L

20–30 years

Requires corrosion protection

Fiberglass

5,000–40,000 L

30+ years

High strength, higher cost

Installation Process for Homeowners

Installing a rainwater harvesting system is a construction and plumbing project that should be planned in stages. The first stage is assessment.

This includes measuring roof area, reviewing historical rainfall data, and identifying intended uses.

Outdoor irrigation requires less treatment and pressure than indoor applications, which influences system complexity. The second stage is layout and sizing.

Tank volume should balance rainfall patterns and household demand rather than aiming for maximum theoretical capture.

During installation, gutters and downspouts may need upgrades to handle higher flow rates. First-flush diverters and filters are installed upstream of storage.

Tanks must sit on a stable, level base capable of supporting their full weight when filled, which can exceed ten metric tons for larger cisterns.

Pumps, pressure tanks, and backflow prevention devices are installed according to local plumbing codes. Electrical connections for pumps must comply with safety standards, particularly in outdoor or damp environments.

In many regions, permits are required for indoor use systems or underground tanks. Plumbing codes often mandate physical separation between rainwater and potable water lines, sometimes with color-coded piping.

Indoor Versus Outdoor Water Use

Rainwater harvesting systems are commonly divided into outdoor-only and combined indoor-outdoor systems.

Outdoor use includes irrigation, car washing, and general cleaning. These applications account for a substantial portion of residential water consumption, especially in dry summers.

Indoor use extends the system to toilets, washing machines, and, in advanced setups, showers and sinks.

Typical Household Water Use Allocation

Use Category

Share of Total Use

Toilet flushing

24–30%

Laundry

15–20%

Outdoor irrigation

20–40% (seasonal)

Bath and shower

20–25%

Other indoor uses

5–10%

Targeting toilets and laundry alone can offset nearly half of a household’s potable water demand without requiring drinking-water-grade treatment.

Water Quality and Health Considerations

Rainwater is naturally soft and low in dissolved minerals, but it is not sterile. Contaminants can enter from roof surfaces, airborne dust, and storage tanks.

For outdoor use, basic filtration is generally sufficient. Indoor use requires more rigorous treatment. Sediment filters remove particulates, carbon filters reduce organic compounds, and ultraviolet systems inactivate bacteria and viruses without chemical additives.

Health authorities in many countries recommend regular system maintenance, including tank inspection and filter replacement.

Studies conducted in Australia and Germany, where residential rainwater use is widespread, show that well-maintained systems do not present higher health risks than municipal water for non-potable applications.

Financial Costs and Long-Term Savings

The upfront cost of a residential rainwater harvesting system varies widely. Small barrel-based systems may cost a few hundred euros or dollars.

Fully integrated systems with underground storage and indoor plumbing can exceed several thousand.

Typical Cost Ranges

System Type

Installed Cost Range

Basic rain barrels

€200–€800

Outdoor irrigation system

€1,000–€3,000

Indoor non-potable system

€3,000–€8,000

Whole-house treated system

€8,000–€15,000+

Operating costs are low, primarily electricity for pumps and periodic filter replacement. In regions with high water tariffs or frequent drought restrictions, payback periods of 5 to 10 years are common.

In areas with low water prices, financial returns may be slower, but resilience benefits remain.

Environmental and Infrastructure Impact

View this post on Instagram

Rainwater harvesting reduces demand on centralized water treatment plants and distribution networks.

This lowers the energy use associated with pumping and treatment. It also reduces stormwater runoff, which helps mitigate urban flooding and erosion.

In cities with combined sewer systems, diverting roof runoff into storage rather than sewers can reduce overflow events during heavy rainfall.

From a climate adaptation perspective, decentralized water storage improves household resilience. During supply interruptions or heatwaves, stored rainwater provides a buffer that centralized systems cannot always guarantee.

Legal and Regulatory Landscape

Regulation of rainwater harvesting varies by country and sometimes by municipality. In Germany and parts of Australia, systems are explicitly encouraged, with standards for design and maintenance.

In some U.S. states, legal frameworks evolved during the 2000s and 2010s to clarify ownership and use rights for captured rainwater. Most regulations focus on preventing cross-contamination with potable supplies and ensuring the structural safety of tanks.

Homeowners considering indoor use should consult local plumbing codes and health department guidelines before installation.

Maintenance Requirements Over Time

A rainwater harvesting system is not maintenance-free, but the workload is predictable. Gutters and screens should be cleared of debris several times per year.

Filters require inspection and replacement according to manufacturer schedules. Tanks should be checked annually for sediment buildup and structural integrity.

Pumps and controls benefit from periodic testing, particularly before dry seasons when reliance on stored water increases.

Neglecting maintenance reduces water quality and system lifespan, but routine care keeps long-term costs low.

When Rainwater Harvesting Makes Sense for Homeowners

Rainwater harvesting is most effective for homeowners with sufficient roof area, moderate to high rainfall, and regular outdoor water demand.

It is also well-suited to households seeking redundancy in water supply or compliance with local sustainability targets. In dense urban settings with limited space, underground systems can still be viable, though costs are higher.

From my own experience reviewing residential water use data, the most consistent benefit is not absolute independence from municipal water but a measurable reduction in peak demand and greater control over household water use patterns.

Conclusion: Practical Value of Rainwater Harvesting Systems

@crubkerb Check out my DIY rainwater harvesting system! Reposted for better editing! Follow if you’d like to see more stuff like this! #DIY #gardening #garden #backyard #rain #rainwater #rainwatercollecting #rainbarrel #water #fyp #fypシ #WaterConservation #SustainableLiving #EcoFriendly #diyideas #tiktokdiy #LearnOnTikTok #foryoupage ♬ Make It Better (Instrumental) – Anderson .Paak

Rainwater harvesting systems provide homeowners with a technically mature, well-documented method to reduce potable water consumption, manage costs, and improve resilience.

When properly designed and maintained, these systems operate quietly in the background, supplying water for everyday uses that do not require drinking-water quality.

The decision to install one should be based on local rainfall, regulatory conditions, and household water habits rather than assumptions or trends.